NWP Monthly Digest | October 2023

Everyone is unhappy, again

Everyone is unhappy again. No surprise, I suppose. This is the world we live in. Last year, it was inflation. This year, not coincidentally, it’s interest rates. The medicine, unfortunately, can sometimes cause just as many problems as the ailment.

Something as big and complex as the United States economy and government is not easily simplified, but it’s important to simplify what we can in order to provide some level of understanding to what’s happening all around us.

Our government and our central bank (The Federal Reserve, or “Fed” for short) can provide two different types of policy responses in a crisis. Fiscal stimulus can be provided by the government and monetary stimulus comes from The Fed. From a very basic standpoint, fiscal stimulus can come in the form of government spending on projects or simply sending checks directly to people’s bank accounts. Monetary stimulus comes from The Fed dialing up or down short-term interest rates that banks charge to each other called “The Fed Funds Rate”, or FFR. There are plenty of other tools that The Fed has up its sleeve to impact the direction of interest rates, but at the end of the day, it’s all about interest rates as far as how they attempt to control monetary policy.

Inflation started to show up aggressively at the end of 2021, ultimately peaking last summer at well over 9%. Initially, the term “transitory” was thrown around a lot to describe this latest bout of inflation as supply chain snafus, staffing shortages, and an overall slow recovery by the global economy following the Covid-19 pandemic shutdowns created an assumption that once the supply side of the equation was fixed, inflation would start to retreat. But there was also the extraordinary amount of stimulus being provided in the form of direct checks sent to individual households here in America as well as the gigantic global fiscal and monetary stimulus response around the world that was having a direct impact on the demand side of the equation. While it is never known precisely what causes inflation and to what magnitude, we’re pretty certain that decreasing supply while simultaneously increasing demand will usually create an inflationary spiral. And here we are.

The Fed, while certainly late to the party initially, has unleashed everything in its power to increase interest rates in an effort to slow down the economy. This blunt tool is the only thing they can really do to try and stifle inflation, and if that sounds like The Fed is trying to cause a recession, it’s probably because that’s what they’re trying to do. The Fed increases interest rates to try and slow down the economy to ultimately impact employment. Higher unemployment means lower inflation, and this relationship (one of the Fed’s favorites) is what is known as The Phillips Curve. It also explains why The Fed is so incredibly misunderstood and unpopular.

Likewise, our federal government can control the fiscal side of the equation by reducing spending in times of economic growth and when inflation starts to show up. This happened ever so briefly last year, but the fiscal deficit has exploded in recent months and has created all sorts of ugliness in the nation’s capital, culminating in a showdown over the weekend to extend negotiations and avoid a government shutdown. While the pain will be delayed for 45 more days, I wouldn’t get too excited that we’ll figure out a good solution.

SO WHAT ABOUT THOSE INTEREST RATES?

Regardless of your political affiliation, things are not being handled well in DC these days and it’s getting really bad. For those of us on Main Street, it will likely be an issue of having to contend with higher interest rates on everything from mortgages to car loans for a much longer period of time than was initially thought, and it’s all happening right as student loan payments resume again this month for many Americans.

Americans hate paying interest on our debt and we hate inflation. And maybe more than the other two combined, we hate being told that we can’t borrow money to do things we want to do RIGHT NOW. We are coming off a period of over 20 years of incredibly low interest rates and easy credit, but just because something seemed normal for a long period of time does not mean that it actually is, indeed, normal.

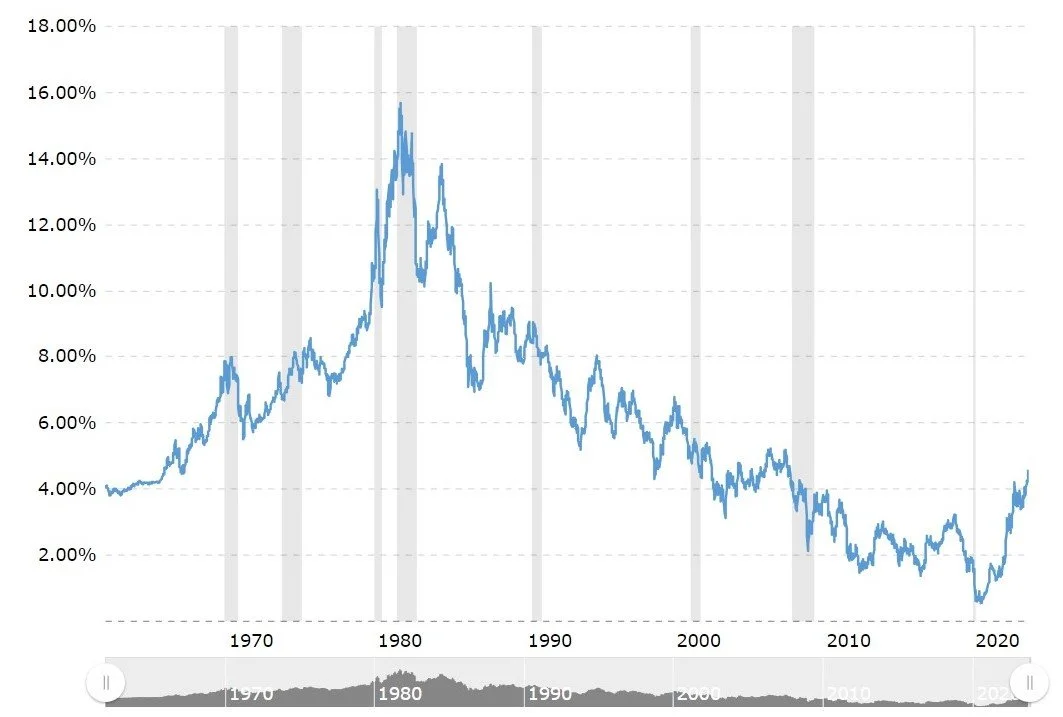

Just take a look at the historical rate on the 10-year US treasury:

Source: Macrotrends.net

As of this writing, the 10-year is sitting at ~4.65%. Higher than we’re used to, certainly, and the highest it’s been since 2007, but not out of the ordinary. If anything, it looks like a slight reversion to normality.

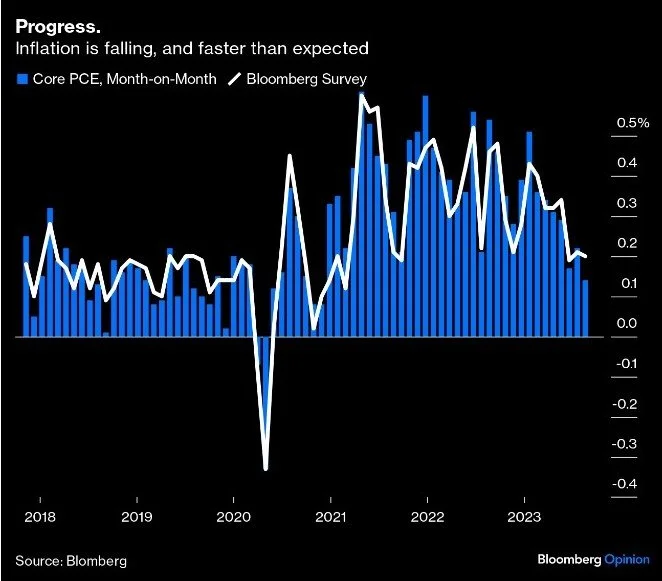

The good news is that inflation seems to have rolled over and the economy just seems to continue to push forward. The bad news is that some of this increase in interest rates has less to do with the fight against inflation and more to do with the fact that United States government may finally have to reconcile and come to terms with our non-stop budget deficits and astoundingly high national debt.

John Authers of Bloomberg and a sensational story this morning about what we can see as the “source” of higher interest rates, and it’s starting to look less and less like a Federal Reserve story and more about a government deficit story.

Inflation has rolled over and it looks like, at least in the short-term, The Fed may get what it wanted in the form of some type of soft landing. Breaking inflation without causing a recession.

But, even with inflation numbers looking much better than we anticipated, the bond market continues to price in higher and higher interest rates. Why? Authers points to a really important concept, called the term premium. In short, the term premium is a measure of compensation that bond investors expect for taking on additional risk on longer-dated bonds or, in other words, the US has to pay higher interest rates to borrow money because investors are getting a little nervous about the future. For a long time, the term premium was negative but just recently turned positive, again.

The US Treasury term premium turned positive last week, which means investors are asking for higher compensation to hold longer-dated securities. While the term premium is not directly observable, we know it is driven by several factors, including: expectations for higher level of rates and rate volatility; concerns around US fiscal trajectory; and slower foreign investor demand precisely at the time when the US Treasury funding needs rise. – Sonia Meskin, Head of US Macro Economics at BNY Mellon Investment Management

In short, the US government is going to have to pay a much higher rate of interest to finance its operations for the time being and farther out into the future than what was assumed, and that means we all will be subjected to higher interest rates for longer than we thought.

HOW DO WE DEAL WITH HIGHER INTEREST RATES?

As mentioned earlier, this is all coinciding with student loan payments returning this month, the first time in almost three years.

As financial planners, we often get questions from clients, prospective clients, and our friends and family surrounding how to maximize the use of their cash. Invest or pay down debt? What is optimal?

In general, we like to flip every debt on its head and look at paying down that debt as a type of investment…meaning, what benefit are we deriving by paying our debt down faster versus investing for the future?

Not surprisingly, the math will always tell you to pay down your highest interest rate debt first. Paying off a car loan with an 8% interest rate and four years left is the same as investing that money and earning 8% per year for the next four years. An 8% guaranteed return on your money is hard to walk away from, and that loan definitely deserves your attention as a place to utilize your excess cash to pay it off in full or more quickly.

A rule of thumb I like to use with my clients is the “5/7” rule. If you have a loan with an interest rate less than 5%, then we will continue to pay that loan on the terms agreed to. If you have a loan with interest rates higher than 7%, then we are going to discuss paying it off immediately or more quickly.

The logic is simple, because the historical real rate of return from the stock market (as measured by the S&P 500 minus inflation) is approximately 6.8%. If the interest on your debt is higher than that number, you should pay off your debt. If it’s lower than that number, you should invest your money instead. Everything is a choice based on the value you can derive. The stock market, of course, does not pay us 6.8% above inflation every year. And because of that uncertainty, a tie should always go to paying off your debt.

This is a question that is going to become very important in future years for everyone.

Noble Wealth Pro Tip of the Month

Normally, October 1st starts the annual FAFSA process for families with children heading to college. This year, however, the Free Application for Federal Student Aid is getting major overhaul. It won’t be available until some time in December, but a final date has not yet been specified.

So what’s changing? You can read more here from the New York Times, but it’s behind a paywall.

The basic summary of the changes:

A more simplified approach with fewer questions

Down with the EFC (effective family contribution) and in with the new SAI (student aid index)

No more discounts for families with more than one kiddo in college

That last one stings. Not just because I’m going to personally have two kids in college next year, but because nobody is prepared for it because we’re not sure how the calculation is going to work. I would advise everyone to expect some major changes and surprises, especially if you have more than one child in college.

It’s troubling that the new formula is going into effect with little warning to students and their parents, Dr. Levine said. “The problem is, you’re flipping a switch,” he said, giving some current students little time to prepare for a potentially larger out-of-pocket bill. Some colleges may be able to adjust financial aid packages to compensate, but that depends on the institution’s finances.

Mark Kantrowitz, a financial-aid expert, said removing the sibling discount had the greatest impact on middle- and high-income students.

Things We’re Reading and Enjoying

Influence, New and Expanded: The Psychology of Persuasion, by Robert Cialdini

The foundational and wildly popular go-to resource for influence and persuasion—a renowned international bestseller, with over 5 million copies sold—now revised, adding: new research, new insights, new examples, and online applications.

In the new edition of this highly acclaimed bestseller, Robert Cialdini—New York Times bestselling author of Pre-Suasion and the seminal expert in the fields of influence and persuasion—explains the psychology of why people say yes and how to apply these insights ethically in business and everyday settings. Using memorable stories and relatable examples, Cialdini makes this crucially important subject surprisingly easy. With Cialdini as a guide, you don't have to be a scientist to learn how to use this science.

-Your team at Noble Wealth Partners

“There is nothing noble about being superior to your fellow man. True nobility is being superior to your former self.” - Ernest Hemingway